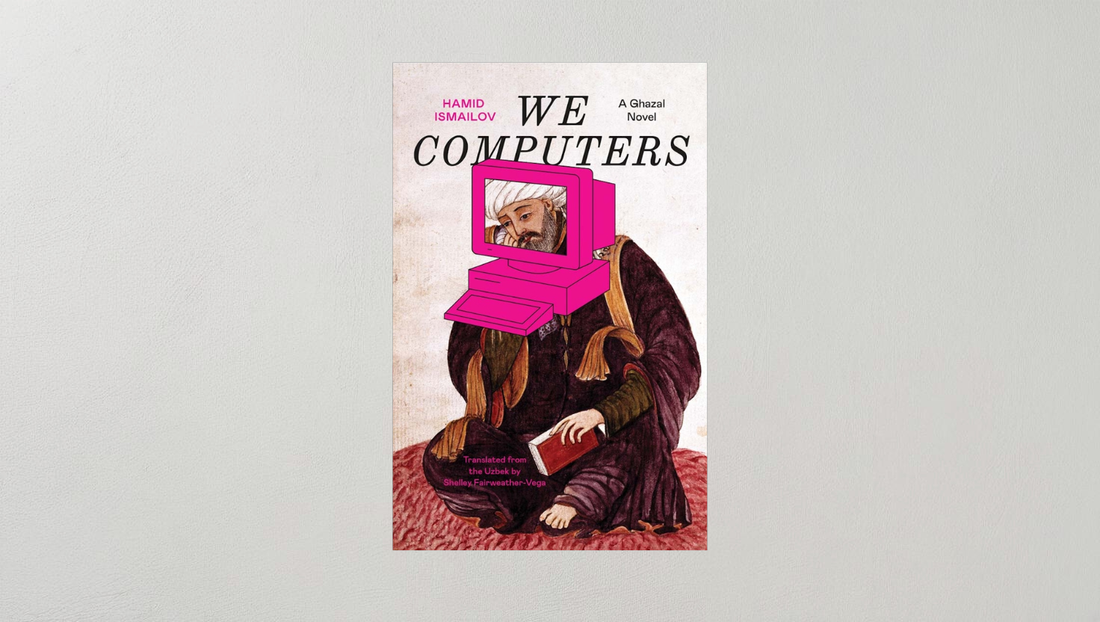

Hamid Ismailov is a poet, journalist and writer from Uzbekistan. His latest novel We Computers: A Ghazal Novel, translated from Uzbek by Shelley Fairweather-Vega, was our October Book of the Month.

We Computers follows a French writer’s quest to discover Persian poetry. Upon acquiring a computer, he starts conjuring entire worlds of literature with the help of AI, until his obsession acquires a mind of its own… Bringing together Ismailov’s encyclopaedic knowledge of Eastern and Western literature, and narrated by a fourth-wall-breaking computer, the novel shapeshifts across genres, cultures, eras and realities.

On 21 October, Hamid joined us at Pushkin House to discuss his novel with Anna Aslanyan. In the lead-up to his talk, Hamid told us what inspired him to write a novel about poetry, programming and psychology; about the tension between AI and creativity; the book’s rich intertextuality; and who really owns a work of literature – the author or the reader?

What are your top five recommended books?

- The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman by Laurence Sterne

- Soul by Andrei Platonov

- Death and the Dervish by Meša Selimović

- The Stranger (L’Étranger) by Albert Camus

- Light in August by William Faulkner

What is a book or poem that inspired you as a young person?

Poems by Sergey Yesenin.

What is a book or poem that takes you back to a specific place or time?

A second-grade Soviet novel Tarantul by G. Matveev that was the first novel which I read clandestinely when I was 6 or 7 years old.

What are you reading at the moment?

Not reading but listening to B. Spinoza’s Ethics. His rational, geometrical way of thinking seemingly preempts our AI.

Which book are you looking forward to reading?

Maqalat by Shams Tabrizi – a medieval Sufi master.

What is your desert island book?

Book of poems by Hafez.

What is a book or poem that cheers you up?

Kalval Mahdum by Abdulla Qadyri in Uzbek. Unfortunately not translated into any other languages.

What is a book or poem you wish you’d written or translated?

Four Quartets by T. S. Eliot.

If you were having a fantasy dinner party, who would you invite?

All poets from my latest novel We Computers.

---

If it’s possible to summarise, We Computers is a novel about poetry, programming and psychology. What inspired you to write it?

I have a long-standing friend, whom I’ve known since the 1990s, and who served as a prototype for the main character of this novel. He was truly at the avant-garde of creating generative poetry, and I was familiar with his work long before the recent hype around AI and the emergence of ChatGPT. Our relationship has always been playful. For instance, in one of his novels he used my name and aspects of my personality to shape his protagonist – and even gave the name of my son to the head of the Parisian mob.

In response, I decided to create a kind of Nasira – a reply of sorts – by incorporating some of his traits into my own work, especially his passion for developing generative poetry. While the majority of the novel is fictional, certain elements of his character inevitably shine through.

At the same time, I wanted to explore the life of Hafez. Since we know little about his biography and only have his poetry, I imagined him as an ideal figure for AI to reflect upon – the eternal tension between a poet’s life and the poetry he leaves behind.

You have always lived, worked and created around multiple languages and cultures. This is reflected in the characters, settings and intertextuality of We Computers – Hafez’s ghazals, the poètes maudits, Arabian Nights and more. Why did you bring these particular elements together?

There is a famous saying: a lion is made of the sheep he has eaten. The same is true of a writer’s world – it is composed of the books he has read, the characters he has encountered in those books, and the whole universe of voices and images that have shaped him. Immersed in this vast culture, the writer inevitably resonates with it: he echoes its themes, converses with its figures, and debates its ideas. The issues may be modern, but they are refracted through the unique angles and perspectives of past experiences and past minds. This interplay is what makes a writer’s inner world so rich.

Your novel sets up a tension between the emotional, romantic world of poetry and the cold, soullessness of technology. Do you see these as mutually exclusive, or did they overlap in ways that surprised you while writing?

Today we are debating what distinguishes AI from the human mind, and there are many perspectives on this question. One should remember that AI is built on logic –on linear, almost geometrical reasoning – whereas the human mind is far more complex. It is driven not only by intellect but also by emotions, intuition, and even mysticism, all of which intertwine and, in many ways, guide our thinking. Here one might also speak of consciousness and the unconscious .

In this sense, the contrast becomes especially interesting to explore. When it comes to logic, AI and the human mind interact and even overlap. But when it comes to the “cloudy” realm – the emotional, intuitive, and unconscious dimensions of the human psyche – the difference is striking. This realisation emerged for me almost like a discovery as I was writing this novel.

Since you wrote We Computers a few years ago, writing about the dangers of AI has become all the hype. However, the idea of the terrifying power of machines has been explored in fiction for a long time. Were you inspired by any other authors or works?

Above all, I was inspired by my friend who had been creating generative poetry since the 1980s. His ideas and experiments kept me within the orbit of his thinking. When I later decided to nominate him for a literary prize, I delved deeply into the subject of AI, conducting quite a bit of research.

At the same time, I had long been a devoted reader of science fiction – especially the works of Isaac Asimov, which I loved most of all. Yet my own book is not science fiction. Rather, it is about the human relationship with technology as it unfolds in reality, not in fantasy.

A central question of the book is about authorship and ownership: about the relationship between an author and their creation, and whether their work and life can be separated. Did you come to a conclusion on whether literature can be, as the narrator puts it, “freed from the chains of authorship?”

This dilemma takes many forms. Formalist schools, structuralism, and French philosophy Barthes, for example – all argued that the life of the author has no real significance for creation. Literature, they claimed, is simply a combination of words.

My main character shares this view: he believes that it is ultimately his computer, his AI, that creates poetry – poetry which is then interpreted freely by the reader, without any pressure from the author. And yet, in a way, the author still exists – transformed, perhaps, into the form of AI itself.

At its core, this is a problem of choice. In the tradition of Oriental poetry, for example, everything is considered to belong to God, and poets are merely transmitters of divine knowledge. In the West, however, the idea of ownership prevails, and with it, authorship as a form of possession.

Ultimately, it is a matter of perspective. I am not taking sides; I simply present these different ways of looking at the issue.

“The poem is just a costume a reader puts on”. There is an interactive, meta quality to We Computers and several passages highlight that it is the reader, not the author, who controls the meaning of a text. Why did you choose this approach, and how do you see the role of reader interpretation in shaping meaning?

In any case, whether the reader engages with a text attributed to an author, to AI, or to an anonymous source, it is always the reader who ultimately transcribes meaning. I can refer to my own experience here. My novels are often read in entirely different ways by different audiences.

For instance, take my book A Poet and Bin Laden. In the West, many readers described it as impenetrable, too difficult to understand or to identify with. Yet in Pashto, where it was translated twice, it became something of a hit, widely read and embraced. One never knows how readers will interpret a work.

Even in smaller cases, readers discover unexpected connections. For example, when my novel The Underground was translated into Italian, one reviewer noted striking similarities with Dante’s Divine Comedy. I had never thought of such a parallel, but readers bring their own cultures, perspectives, and experiences into the act of interpretation. In fact even We Computers which we are discussing is a wonderful English interpretation of the Uzbek original by Shelley Fairweather-Vega.

Your books are banned in Uzbekistan, and you have had to publish the original novels serially on social media. How have they been received by your readers in Uzbekistan? And how do you feel about social media as a publishing medium?

Different books make different kinds of impact on social media. For example, when I published The Devil’s Dance on Facebook, it sparked a lot of debates, reposts, and even republications in newspapers. One group of women in Uzbekistan was fiercely debating with another group of young Uzbek women – it really created a lot of hype.

However, when I published it on Telegram, around a thousand people subscribed, but I didn’t know what their reactions were since there was no feedback option. That effort was more about making people aware of the book rather than reaching a wide audience.

Can you tell us a bit about the ghazal and its multilayered presence in the novel?

To put it simply, the ghazal can be seen through the lens of Roman Jakobson’s scheme of communication. At its core, it is a message of love that flows from the lover to the beloved. Its reference point is separation, and around it there are forces – some aiding the lover, others opposing him.

In this sense, the ghazal reflects the structure of any human activity. In every endeavour, there is a goal to be reached, obstacles that stand in the way, and forces that offer support. The reference point may vary – it can be scientific, social, ethical, or something else entirely – but the underlying dynamic remains the same.

Thus, the ghazal as a universal form touches the very essence of human existence and its relationship with love – whether that love is directed toward a woman, a man, or the Absolute.

Meaning is an elusive concept throughout We Computers. Unreliable narrators and characters abound. Why do you involve such ambiguity, uncertainty, or as it’s called in the book, “glimmering”?

One of the central features of the ghazal – and the reason my novel is called A Ghazal Novel – is this quality of glimmering or ambiguity. It is, in many ways, akin to the sfumato of the Renaissance: a way of living within paradox, of being neither entirely here nor there.

Think, for example, of Raphael’s Madonnas. On the one hand, they offer the child to humanity; on the other, the Madonna protects him fiercely. She seems to move toward you, yet at the same time she withdraws, as though trying to escape your gaze. This sfumato technique – this play of presence and absence – belongs to an era when humanity was balancing between scientific, rational knowledge and the forces of mysticism.

In the same way, the human mind itself has always shifted between these two modes of thought and perception. That is why it was so important for me to make this glimmering, this ambiguity, a defining trait of my novel as well.

Did you use AI in the process of writing We Computers?

No, it wasn’t there yet.

What are you working on next?

After completing We Computers, I entered a particularly productive period and wrote not one but three novels.

The first reflects on my experience as a child reader, when I encountered Matveev’s Tarantul. I examined the traces it left on me, the techniques of Soviet brainwashing embedded in it, and how I later worked to cleanse my mind of that propaganda. It’s called Tarantul’s Bite.

The second novel grew out of my unfinished works. I sought to uncover the logic behind why, in my youth, I left certain pieces incomplete. By revisiting those fragments, I revealed the reasoning behind their incompletion. This book became Mother, Daughter, and Sinful Soul.

The third novel once again engages with AI. Here I explored the differences between the human mind and artificial intelligence through the lens of a Sufi allegory – Fariduddin Attar’s The Conference of the Birds (The Logic of Birds).

1 Comment

Wonderful interview! Good luck with the event at Pushkin House!