Dr Carol Adlam is Associate Professor in the Nottingham School of Art & Design. She formerly worked as a university lecturer specialising in Russian literature and art, before embarking on a second career as an award-winning artist and illustrator.

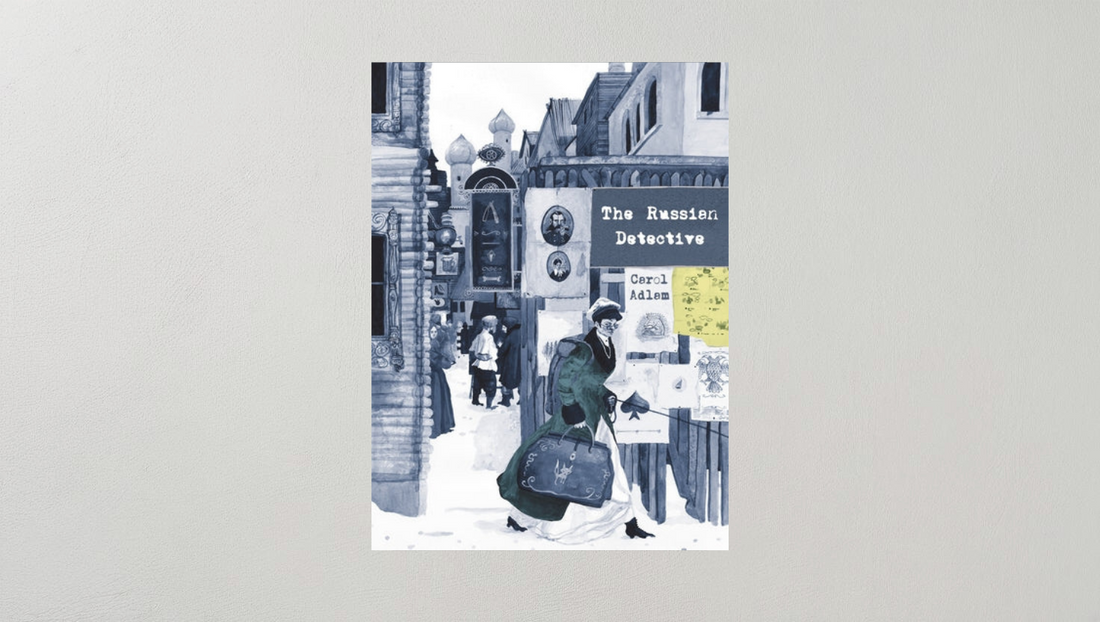

Carol will be presenting her latest book, The Russian Detective, a graphic novel adaptation of a bestselling 19th-century crime novel, at Pushkin House on 21 June. In the lead-up to her event Carol has told us about the story behind her book, as well as sharing her favourite books, literary inspirations and more.

What are your top five recommended books?

- Currently, JG Farrell, The Siege of Krishnapur

- Hilary Mantel, The Mirror and the Light

- Rebecca d’Autremer, Des souris et des hommes

- Isobel Armstrong, Glassworlds

- Peter Carey, True History of the Kelly Gang

What is a book that inspired you as a child or young person?

Goscinny and Uderzo, Asterix and Cleopatra.

What is a book that takes you back to a specific place or time?

Patrick White, A Fringe of Leaves.

Which book are you looking forward to reading?

Elly Griffiths, The Last Word.

What is your desert island book?

The largest historical world atlas it’s possible to be washed on shore with (or possibly on).

What is a book or poem that cheers you up?

Geoffrey Willans and Ronald Searle, Molesworth

What is a book you wish you’d written?

Bernadine Evaristo, The Emperor’s Babe.

If you were having a fantasy dinner party, who would you invite?

Hilary Mantel; EF Benson; Anton Chekhov. I’d spend a lot of time in the kitchen, taking notes.

What inspired your interest in Russia, and what is your background in Russian literature?

I grew up in Melbourne, Australia, which had a very large number of immigrants who had come from the Soviet Bloc. From my earliest school through to university many of my teachers were Russian, as well as Czech, Lithuanian, Bulgarian, and Polish. They taught me many subjects, including Russian language, which I started learning from the age of 11. I went on to do an undergraduate degree in Russian at Durham University, followed by a PhD, and after that I had a first career as a lecturer at various universities, where I specialised in Russian literature and art (nineteenth century, and post-Soviet).

Why did you decide to write The Russian Detective?

For three decades somewhere in the back of my mind there’s been Charlotta Ivanovna – the strange governess from The Cherry Orchard, who is a quintessential outsider figure. And for years I was intrigued by accounts of Russia’s contradictory visual cultures during this period. And then I re-encountered Claire Whitehead, who is a specialist on early crime fiction in the post-reform period at St Andrews University. Claire asked me to do the cover of her book on that subject, and I then proposed a graphic adaptation of one of the books she was working on.

That turned into the much more extensive text and multi-media adaptation project at the University of St Andrews, "Lost Detectives: Adapting Old Texts to New Media", which ran between 2019–2023, and for which I made various audio and text adaptations. The Russian Detective grew out of that, and through it I was able to bring together all of these elements that have intrigued me for so long – so Charlotta becomes Charlie Fox, my protagonist, and the adaptation sits in a Russian doll-like structure, somewhere in the heart of the book, which is also about visuality and change, and illusion, and trickery.

How is it to approach Russian literature through an artist’s eyes rather than from an academic perspective?

It’s liberating and thrilling! Although I should say that my work always starts deep in the archives before I get to the drawing board. While I don’t feel the same obligations to "accuracy" (or in the case of adaptation, "fidelity") that I would as an academic, I do want the work to reflect my own deeply researched understanding of historical patterns of thought and representation. But you can say things through image and creative text that you often would hesitate to do as an academic, with far greater reach. Images are wonderful because they can point out holes in historical records or paradoxes in an instant, and creative writing also allows you to be irreverent in a way that academic writing rarely does.

So Russian literary culture runs through The Russian Detective via multiple allusions: for instance, the preface shows the very strange censor’s mark described at the end of Turgenev’s Diary of a Superfluous Man; Dostoevsky is a bit-part character on a train who is arrested early on; elsewhere I have a seamstress who makes asides on all her difficult customers, including Mrs Karenina, Miss Larina, Mrs Ranevskaya ("a bit of a nightmare, between you and me"), and I also talk about "low" literary culture – including crime fiction – through the disreputable newspaper that Charlie Fox works for, the Daily Balalaika, which is based on Peterburgskii listok. It’s a bit like poetry – through the interplay of text and image multiple meanings can be layered and condensed.

How does Semyon Panov’s story, and the period it is set in, lend itself to adaptation as a graphic novel?

Panov’s work is a baggy sort of work featuring a hapless judicial investigator and a police officer, numerous red herrings, and it centres around the idea that women’s sexual jealousy can lead to acts of extreme violence. In terms of themes and psychological motivation it’s very hard to make it palatable for a modern audience. Structurally, too, it’s a tough call. Readers coming from the western tradition don’t want to know too early on who did the crime, and tend not to want lengthy philosophising about crime and society after that. Even the duo of the judicial investigator and police officer don’t make sense to a western reader – they don’t map on to a Holmes and Watson pattern, because these two figures were both arms of the state, with very different jurisdictions and responsibilities that arose out of the 1860s reforms.

It took me three different versions of the script before I realised that all this just wouldn’t work and that I needed to move away from that idea of "adaptation" altogether. That’s when I threw caution to the wind and made radical changes, the most important of which was that I embedded Panov’s story (a very loose version of it!) within my own story about Charlie Fox, because she was the means by which I could comment on the wider genre of crime fiction, and how it intersected with newspaper culture and undercover journalism. So Panov’s story is the crime that Charlie Fox investigates, but the book is about far more than that.

The book is full of textures and different artistic techniques and styles that bring the story to life. Could you tell us about a couple of them, and why you chose them?

The book is as much about visual culture as it is about literary culture. I wanted to show that the visual culture of this period was rich, diverse, and really exciting – not only is there a revolt in Academy of Arts by students who reject classicism and inaugurate the period of high naturalism that we associate with Repin, Vereshchagin, etc – but popular visual culture was flourishing in all sorts of ways as new technologies appeared alongside older ones.

So I show lubki and street signs and newspapers and photos and optical toys, and my characters go to the Magic Lantern show, and the townspeople gawp at a peepshow (raek), and I and even have an anamorphic illusion buried in the book as well. I wanted to use these devices to pull the reader deeper into the story, to tell and re-tell the story, and to make you turn back the page and reconsider what you might think you know. To make them I used all sorts of different media, from large charcoal drawings to paintings in gouache. I even made an actual peepshow, which I then photographed. I drew, painted or made everything by hand, and then worked digitally.

The Russian Detective’s protagonist is the journalist-detective Charlotta Ivanovna (aka Charlie Fox). Why did you make her the heroine of the story?

As I said, Charlie Fox has been wandering around in my head for almost three decades now, ever since I was a student … so when I started to think about framing Panov’s work, she appeared before me. My Charlie is a magician as well, and a bit amoral, and she doesn’t know where she’s from. She is rootless, and all she has in the world is her little dog, Igoryok. She’s tough, but that’s her vulnerability as well, and in the course of this book, she finds out who she really is and that makes her flee to Siberia in a hot air balloon…

The only other thing Charlie cares about is her job as a journalist. I made her a journalist because I’d been reading about the countless women who were hired in early newspaper offices in Russia and elsewhere to go undercover as investigative journalists, because women could pass unnoticed. Nellie Bly is an example people might have heard of in the UK. Russia didn’t have women detectives or police until the Revolutionary period, so Charlie isn’t a detective as such, although she is forced by circumstances to become the investigator of what is going on around her.

When we think of 19th-century Russian literature, the names that come to mind are Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Turgenev, Chekhov… How does your book contribute to our understanding of writing of that period?

I hope it will give people a sense that there was much more going on at that time, and that pulp or "low" fiction was just as important as the works we now think of as ‘canonical’. There’s much more to be found out about this period, particularly on the role of women in crime fiction and other genre fiction – which is what Claire Whitehead and I, with Mona Bozdog at Abertay University, hope to explore in other media as well.