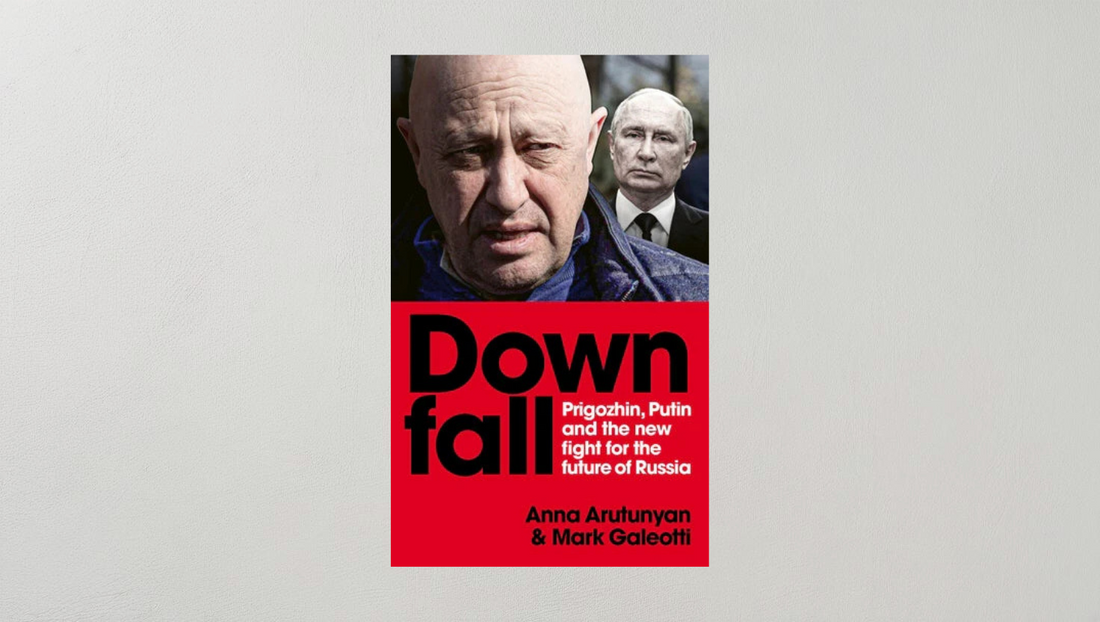

Anna Arutunyan, a journalist and analyst, and Mark Galeotti, a specialist on the Russian military and security services, tell us about their recommended reads for business and pleasure and their new book Downfall: Prigozhin, Putin, and the New Fight for the Future of Russia which they will be discussing at Pushkin House on 22 October.

What are your top five recommended books?

Mark: Gosh, an impossible ask; apart from the fact that they change from day to day, there are books that enlighten, books that entertain, books that uplift. Arbitrarily picking from the best of the bunch…

-

W. Bruce Lincoln’s Nicholas I for its combination of readability and scholarship, proving that one can be empathic without being approving

-

Karen Dawisha’s Putin’s Kleptocracy for marrying synthesis and discovery and avoiding cheap hyperbole

-

Peter Vansittart’s Worlds and Underworlds: Anglo-European History Through the Centuries for a sometimes barking mad but always entertaining game of historical connections

-

Federico Varese’s Mafia Life for a look beneath the clichés and cheap assumptions about what drives gangsters

- Lois McMaster Bujold’s Memory for a science fiction book that is more about growth and relationships than gadgets.

What is a book that inspired you as a young person?

Anna: Tolkien’s The Silmarillion, for its depth of thought and language.

What is a book that takes you back to a specific place or time?

Mark: Martin Walker’s Russia (Penguin, 1989), a collection of his columns for The Guardian as its Moscow correspondent. As someone who really came into studying the field during the perestroika years, there’s a wonderful, if now wistful optimism in these dispatches.

Which book are you looking forward to reading?

Anna: Jack Margolin’s new book The Wagner Group for professional reasons, and George Macdonald Fraser’s Flashman series for pleasure.

What is your desert island book?

Mark: I’d be tempted to say anything that teaches me to survive on a desert island, but in the spirit of the question, Dominic Lieven’s In the Shadow of the Gods: The Emperor in World History as one reading wasn’t enough.

What is a book or poem that cheers you up?

Anna: Put Me in the Zoo by Dr. Seuss (although Mark would make a case for his Oh The Places You’ll Go)

What is a book you wish you’d written?

Mark: Whichever one I still have to write next…

If you were having a fantasy dinner party, who would you invite?

Anna: Nicholas I and Putin, but only as long as Prigozhin is catering and overseeing the service.

When and why did you decide to write about Prigozhin?

Mark: The irony is that initially we were reluctant to do so, even though several people were urging us in that direction. Why spend so much time immersing ourselves in the life of such an unpleasant man? Thinking about it, though, we realised that using Prigozhin’s life, from convict through businessman and trollmaster to mercenary entrepreneur, we could illuminate the evolution of Putin’s regime, and the crucial role played by the minigarchs and adhocrats who benefit from it. We ended up signing the contract two weeks before his mutiny upended everything!

Is he a unique figure in Russian history?

Anna: No, he’s not. In many ways he fits into an historical tradition of the opportunistic agent of the tsar who turns against the state when he feels betrayed, someone like Emelyan Pugachev.

Prigozhin started out as a criminal and died a criminal; was his violent downfall inevitable?

Mark: Nothing is ever inevitable. Had he not been tapped by the Kremlin to organise what became Wagner, he might have remained another grasping and corrupt entrepreneur among many, but certainly his aggressive ways and his inability to abandon his feuds, whether with Shoigu on ‘grandpa,’ led to his fiery downfall.

Did the Wagner rebellion illuminate any assumptions or misunderstandings about Russia’s political system?

Anna: It highlighted the mistaken assumption that Putin is in control, but is about to lose it. The mutiny demonstrated that, in fact, the Kremlin's control is always much weaker than assumed. The mutiny's aftermath demonstrated that Putin has become adept at manoeuvring within this limited control, often using the state’s fragility as a strength.

Will Prigozhin and his rebellion have any long-term impact?

Mark: Yes. He highlighted Putin’s decaying capacities to manage intra-elite disputes – which were always central to his rule – and punctured the notion that he has the absolute and enthusiastic support of the security forces, as in the main they were willing to sit back and see what happened.

Prigozhin died midway through your writing process; did you see it coming?

Anna: After his mutiny, it was distinctly unlikely he would go on to live a long and happy life, but given the deal he had struck with Putin, we didn’t think he would die quite so soon.

Are there other figures who could challenge Putin for power?

Mark: Of course, but no one will advertise it, and it wouldn’t be easy. One thing this system is good at is securing itself, and with no Communist Party to create a framework for any such challenge, unless and until there is a real nation-shaking crisis, it will be easier to keep a low profile and wait for nature to create a power vacuum.

Which books would you recommend to help us understand what is happening in Russia and Ukraine, or which academics/ journalists/ activists should we pay attention to?

Anna: There are the obvious choices like Mikhail Zygar, but it is too easy to go for the Western-looking (and increasingly émigré) liberals; we also need to understand what the nationalists like Igor ‘Strelkov’ Girkin, Egor Holmogorov and the now-deceased Konstantin Krylov say. It may not be as comfortable, but it’s important.